Architectural Drawing: From Soane’s Time to Today

As an online retrospective of The Architecture Drawing Prize opens in the Vault of Contemporary Art, Sir John Soane’s Museum’s Curator of Drawings and Books, Frances Sands, and Curator of Exhibitions, Louise Stewart, explore the role of architectural drawings in the work and collection of Sir John Soane and their parallels today.

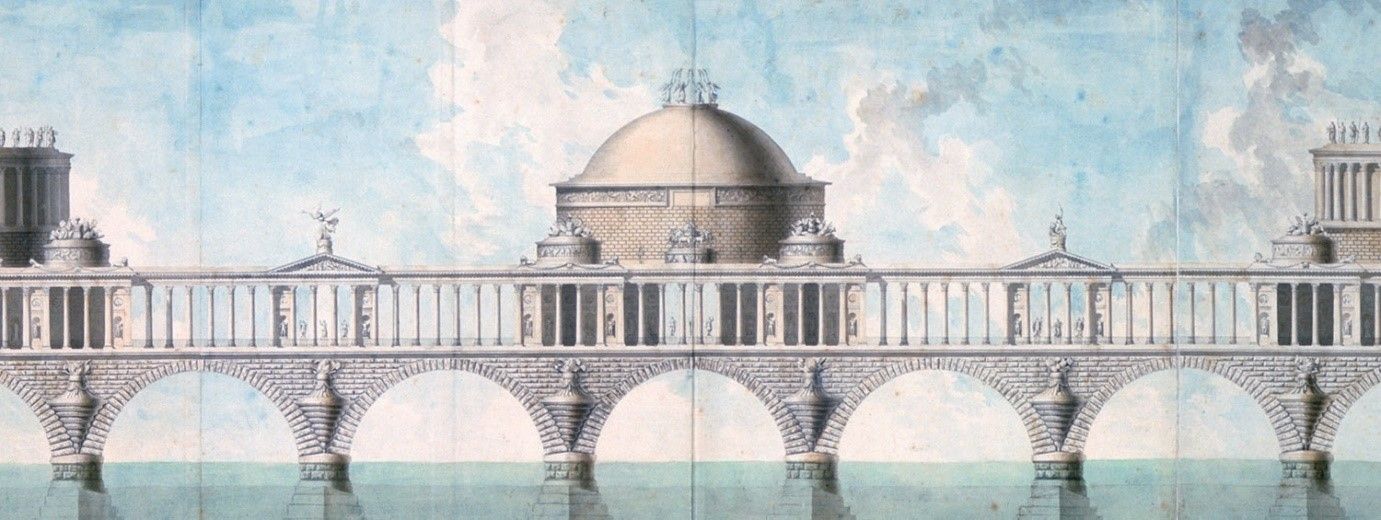

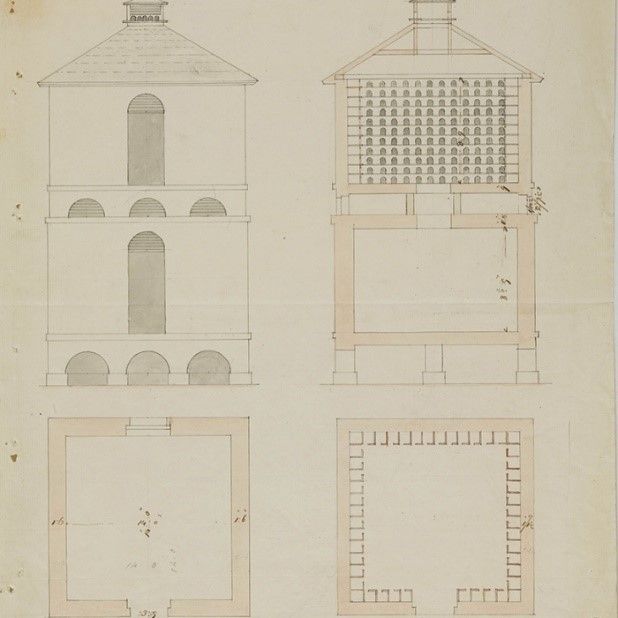

The Architecture Drawing Prize was founded in 2017 as a collaboration between Make Architects, the World Architecture Festival and Sir John Soane’s Museum. Each year, the prize receives hundreds of entries from around the world. It celebrates the significance of drawing as a tool in capturing and communicating architectural ideas. Winning and shortlisted entries are showcased in a special exhibition at Sir John Soane’s Museum, the extraordinary house and museum of the British architect Sir John Soane. Soane understood the importance of architectural drawings. It was his skill in architectural composition and draughtsmanship which propelled him towards professional success, when in 1776, aged only 23, he won the Royal Academy gold medal for architecture with a design for a monumental bridge (Figure 1).

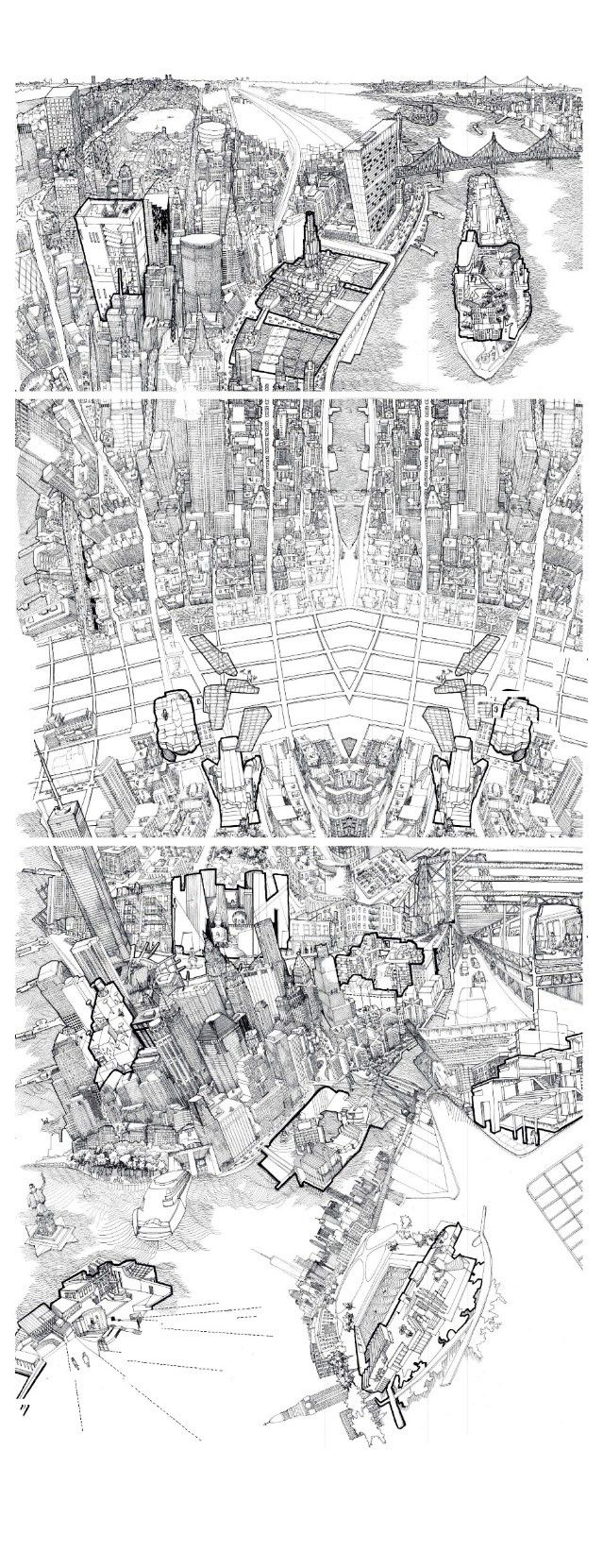

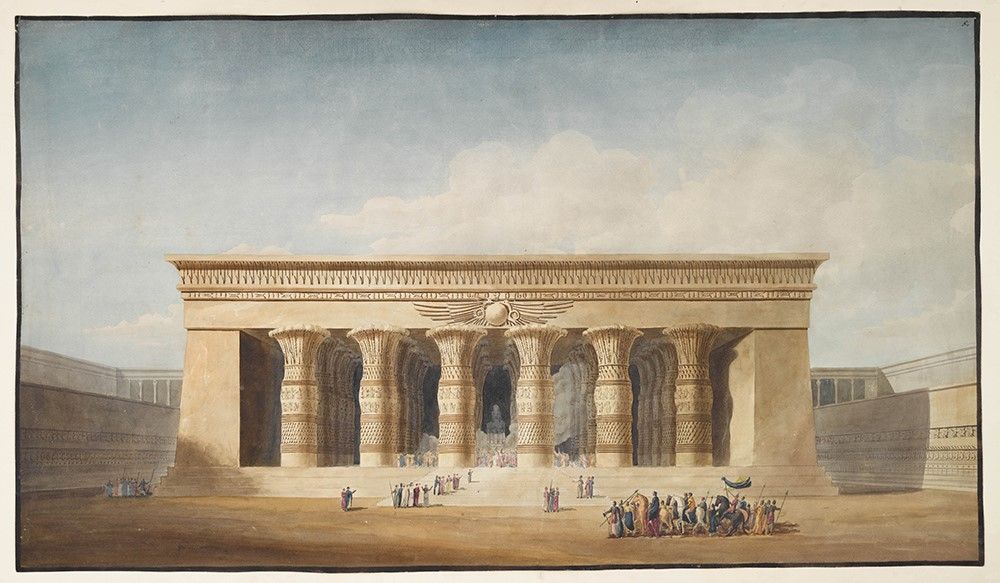

During his career, Soane collected some 22,000 drawings by other significant artists and architects. There are also 8,000 drawings surviving from his own office in the collections of Sir John Soane’s Museum today. As a member of the Royal Academy, Soane exhibited there regularly, with drawings of his architecture by the artist Joseph Michael Gandy. The image of a design for an entrance to London by Gandy (Figure 2) presents one element of Soane’s ambitious but largely unexecuted plan to redesign a swathe of the city as a grand, ceremonial route. Gandy’s drawings offered an idealised version of Soane’s work, devoid of worldly constraints such as budget, plot size or executed status. As such, the mesmerising and frequently fantastical content of The Architecture Drawing Prize entries would have been understood by Soane as kindred spirits to his own work.

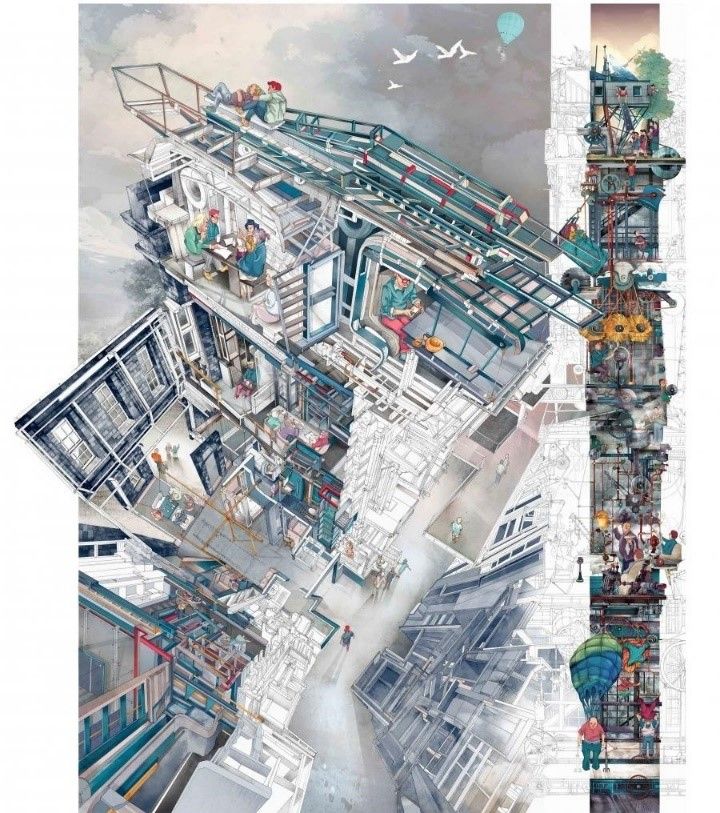

Embassy Nation by Sarmad Suhail (Figure 3), a commended entry in the 2018 Prize, provides a contemporary counterpoint to Soane’s plans for London. It reimagines New York City as a utopian space in which different portions of society interact harmoniously. Both drawings’ proposals reflect the contemporary concerns of the societies in which they were made – celebrating British identity in Soane’s time and migration and integration in the early 21st century.

Less glamorous than Gandy’s exhibition drawings, the everyday work of Soane’s office typically focused on drawings for architectural commissions. In order to keep pace with the number of drawings required of his office, from 1784 Soane accepted articled pupils. He took his teaching responsibilities seriously, stressing the importance of draughtsmanship, accurate estimates and an understanding of construction.

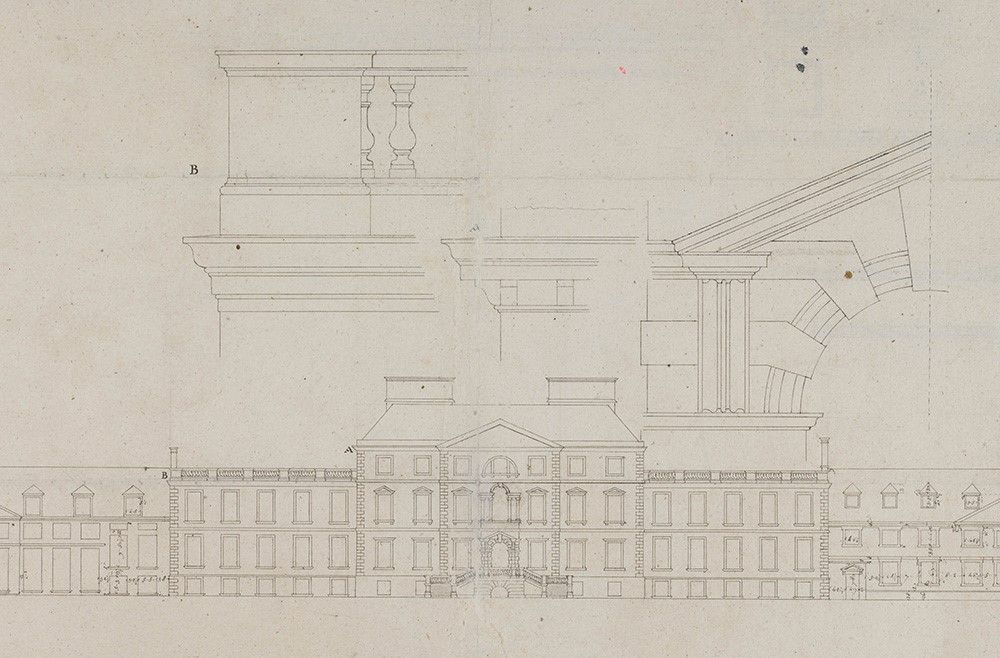

The first stage of a new project involved a draughtsman being sent to the building site to make survey drawings of the topography and pre-existing architecture (Figure 4). This provided Soane with contextual information for his designs. As the function of a survey drawing is to relay an accurate representation, they are drawn simply, without distracting ornamental flourishes.

Following the survey drawings, Soane produced rough preliminary designs to develop his initial ideas, which were then worked up to scale by a draughtsman. Once Soane was satisfied with the composition, a finished drawing – a neat version – was produced. If this finished product met Soane’s approval, it was then presented to the client to explain Soane’s design ideas with the hope of execution. Certain drawing formats are easier for the layperson to interpret than others. The elevation and perspective view, which show the building head on or give a naturalistic pictorial representation of a building in its setting, were particularly useful for presentation to clients (Figure 5).

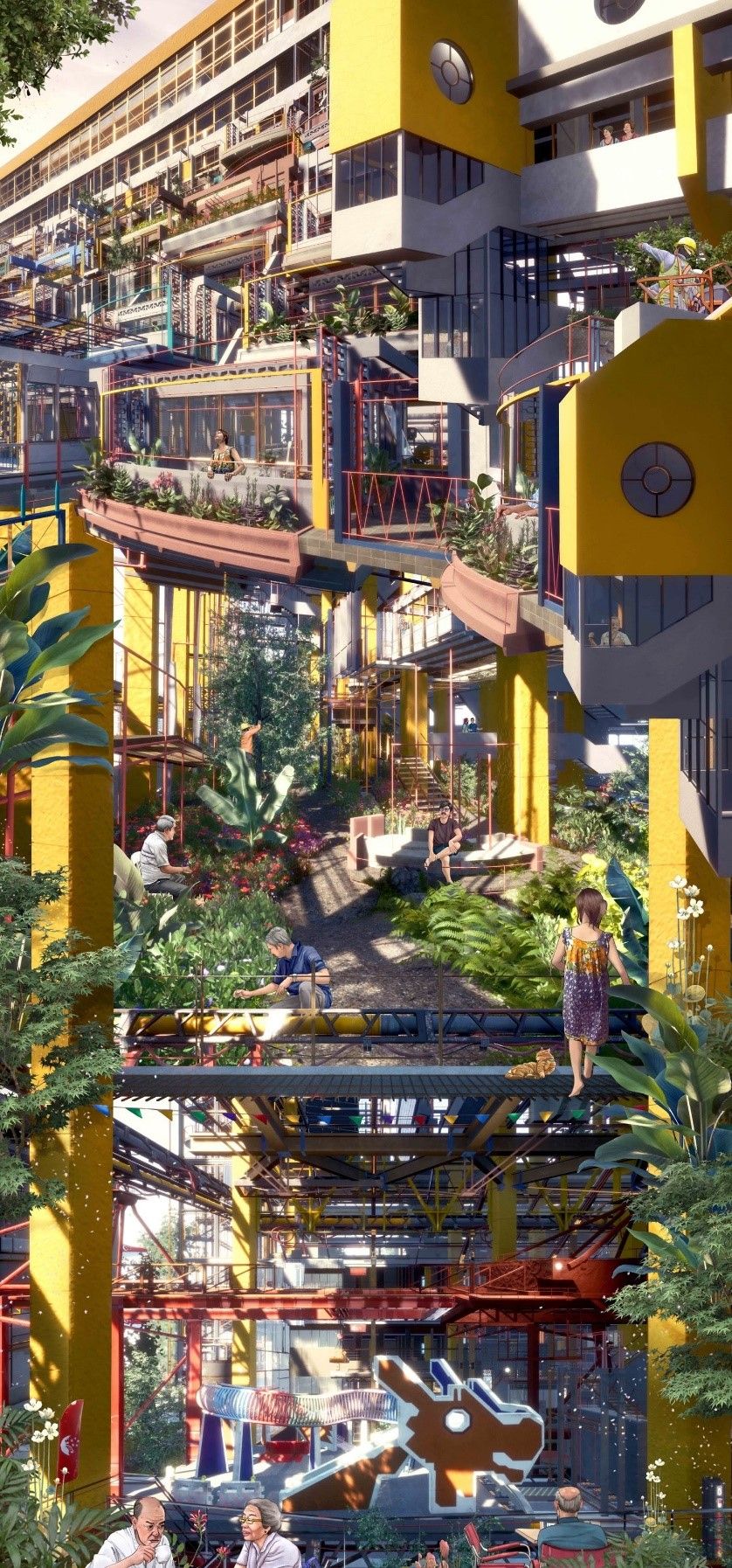

Entries to The Architecture Drawing Prize demonstrate the continuing appeal of these types of drawings, which convey an overall vision for a project in a way that is both easy to understand and highly appealing. Jerome Ng’s proposal for the redevelopment of Singapore’s Golden Mile complex (Figure 6) reimagines a condemned building as a vibrant, busy and sought-after apartment complex.

Should Soane’s client approve the presentation drawings, an entirely new series of working drawings were required. These provided comprehensive instructions to builders and artisans so that Soane’s designs might be faithfully reproduced in three dimensions. The majority of these were plans, elevations, sections or perspective views. A plan illustrates the footprint and sometimes the internal arrangement of a building (Figure 7); a section cuts through a building.

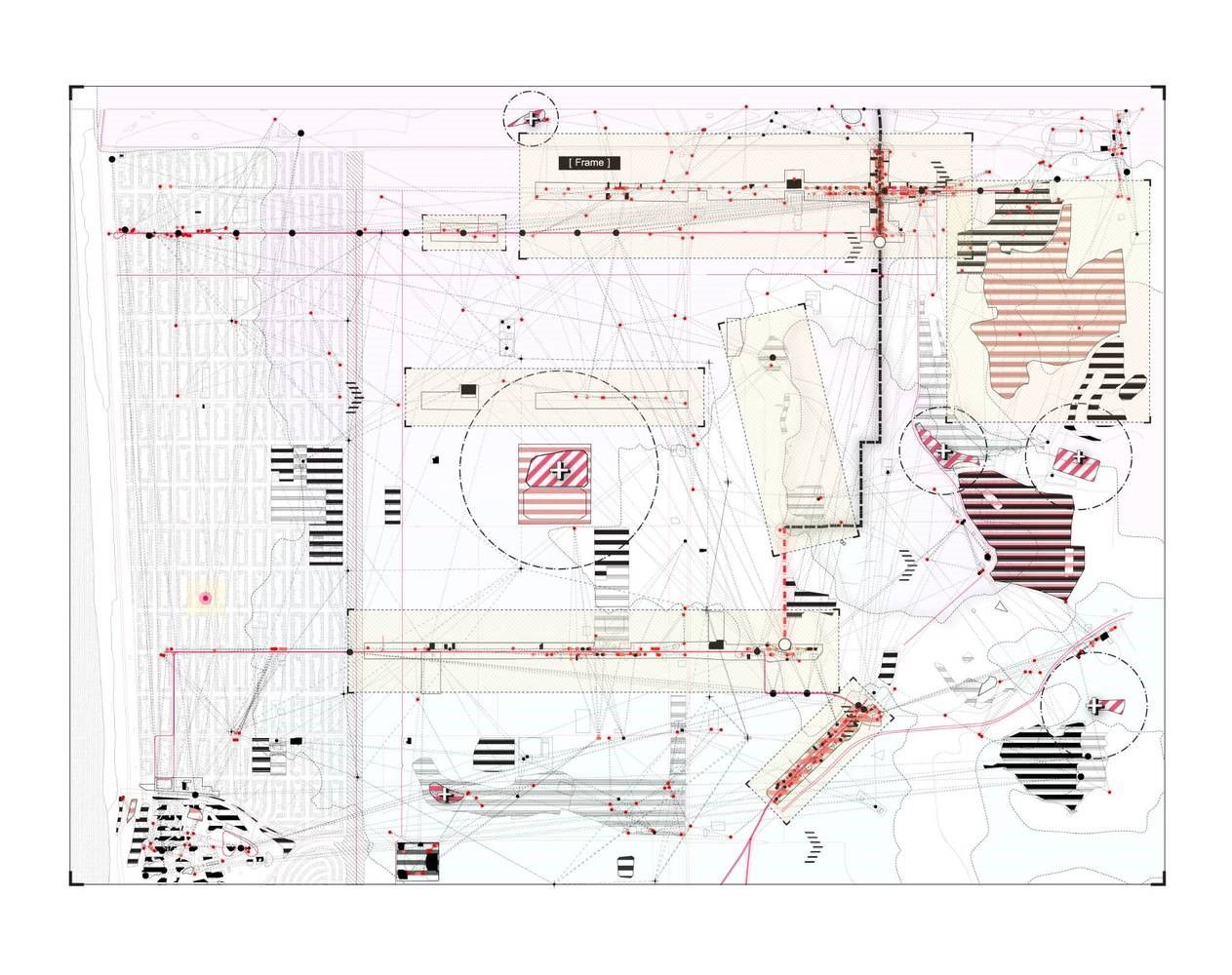

Technical and highly functional, both Soane’s office drawings and entries to The Architecture Drawing Prize demonstrate that plans, sections and site studies can be aesthetically pleasing, original and ambitious. For example, Chenglin Jin’s Re-Reading Metropolis (Figure 8) uses the conventions of a site study to convey an ambitious proposal for changing the way districts in San Francisco relate to one another. Meanwhile, Jerome Ng’s Memento Mori: A Peckham Hospice Care Home (Figure 9) uses sections through the building to demonstrate its potential benefits to its users as well as the way the building is constructed.

In 1806 Soane was elected Professor of Architecture at the RA, an ideal calling for an architect who took such care over training his articled pupils, and he compiled 12 lectures detailing the history of architecture. These were illustrated with large lecture drawings (Figure 10), which are thought to comprise the earliest attempt at a graphic history of world architecture.

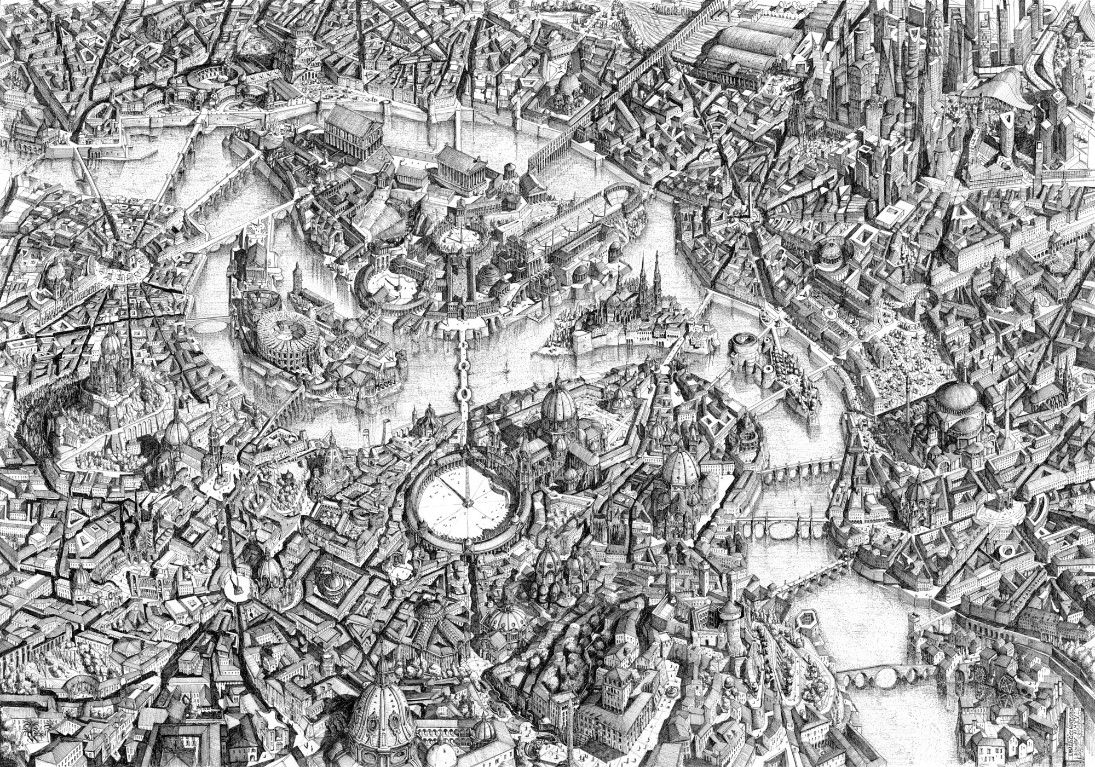

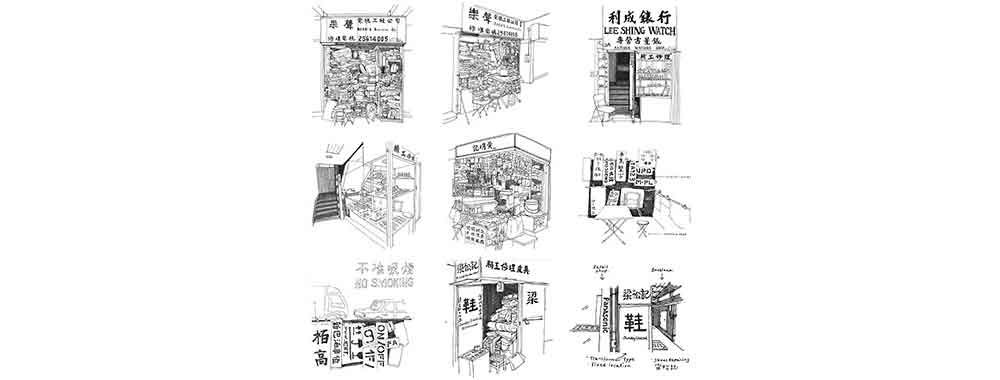

Entries to The Architecture Drawing Prize illustrate the continuing allure of architectural history as a rich source of inspiration for architects today. Ubaldo Occhinegro’s Utopia (Figure 11) imagines a perfect city as a condensed history of western architecture, using ancient temple forms, renaissance domes and piazzas, and contemporary skyscrapers and organic forms. Meanwhile, Man Yan Lam’s work (Figure 12) demonstrates the importance of drawing in preserving lost architecture. His series of drawings of Hong Kong shopfronts record an aspect of the city that is quickly disappearing. This mirrors the many lost buildings preserved through drawings in Soane’s collection, not least his own masterpiece, the Bank of England (Figure 13).

The 8,000 Soane office drawings and over 300 entries to The Architecture Drawing Prize so far illustrate the variety and quality of Georgian and contemporary architecture. Soane preserved his drawings to inform and inspire architects of future generations. They were produced with goose feather pens and horsehair brushes, as opposed to the modern utensils and computer programmes used by the artists of The Architecture Drawing Prize, but Soane would have admired the skill, creativity and understanding of architectural history that is evidently still flourishing.